Pseudoconvex function

In convex analysis and the calculus of variations, branches of mathematics, a pseudoconvex function is a function that behaves like a convex function with respect to finding its local minima, but need not actually be convex. Informally, a differentiable function is pseudoconvex if it is increasing in any direction where it has a positive directional derivative.

Contents |

Formal definition

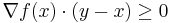

Formally, a real-valued differentiable function ƒ defined on a (nonempty) convex open set X in the finite-dimensional Euclidean space Rn is said to be pseudoconvex if, for all x, y ∈ X such that  , we have

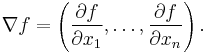

, we have  .[1] Here ∇ƒ is the gradient of ƒ, defined by

.[1] Here ∇ƒ is the gradient of ƒ, defined by

Properties

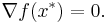

Every convex function is pseudoconvex, but the converse is not true. For example, the function ƒ(x) = x + x3 is pseudoconvex but not convex. Any pseudoconvex function is quasiconvex, but the converse is not true since the function ƒ(x) = x3 is quasiconvex but not pseudoconvex. Pseudoconvexity is primarily of interest because a point x* is a local minimum of a pseudoconvex function ƒ if and only if it is a stationary point of ƒ, which is to say that the gradient of ƒ vanishes at x*:

Generalization to nondifferentiable functions

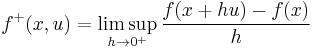

The notion of pseudoconvexity can be generalized to nondifferentiable functions as follows.[3] Given any function ƒ : X → R we can define the upper Dini derivative of ƒ by

where u is any unit vector. The function is said to be pseudoconvex if it is increasing in any direction where the upper Dini derivative is positive. More precisely, this is characterized in terms of the subdifferential ∂ƒ as follows:

- For all x, y ∈ X, if there exists an x* ∈ ∂ƒ(x) such that

then ƒ(x) ≤ ƒ(z) for all z on the line segment adjoining x and y.

then ƒ(x) ≤ ƒ(z) for all z on the line segment adjoining x and y.

Related notions

A pseudoconcave function is a function whose negative is pseudoconvex. A pseudolinear function is a function that is both pseudoconvex and pseudoconcave.[4] For example, linear–fractional programs have pseudolinear objective functions and linear–inequality constraints: These properties allow fractional–linear problems to be solved by a variant of the simplex algorithm (of George B. Dantzig).[5][6][7]

See also

Notes

- ^ Mangasarian 1965

- ^ Mangasarian 1965

- ^ Floudas & Pardalos 2001

- ^ Rapcsak 1991

- ^ Chapter five: Craven, B. D. (1988). Fractional programming. Sigma Series in Applied Mathematics. 4. Berlin: Heldermann Verlag. pp. 145. ISBN 3-88538-404-3. MR949209.

- ^ Kruk, Serge; Wolkowicz, Henry (1999). "Pseudolinear programming". SIAM Review 41 (4): pp. 795-805. doi:10.1137/S0036144598335259. JSTOR 2653207. MR1723002.

- ^ Mathis, Frank H.; Mathis, Lenora Jane (1995). "A nonlinear programming algorithm for hospital management". SIAM Review 37 (2): pp. 230-234. doi:10.1137/1037046. JSTOR 2132826. MR1343214.

References

- Floudas, Christodoulos A.; Pardalos, Panos M. (2001), "Generalized monotone multivalued maps", Encyclopedia of Optimization, Springer, p. 227, ISBN 9780792369325.

- Mangasarian, O. L. (January 1965). "Pseudo-Convex Functions". Journal of the Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics Series A 3 (2): 281–290. doi:10.1137/0303020. ISSN 0363-0129..

- Rapcsak, T. (1991-02-15). "On pseudolinear functions". European Journal of Operational Research 50 (3): 353–360. doi:10.1016/0377-2217(91)90267-Y. ISSN 0377-2217.